The Netherlands Has Entered a New Climate Regime: KNMI 2025 Report

This morning I woke up at 4:30 AM after a fragmented night of sleep, one of those nights where you wake up at 11 PM and your brain decides it’s time to think about everything for a few hours before letting you drift off again. I measured my heart rate variability with my Polar sensor, like I do most mornings now. The numbers told me what my body already knew: I’m running on reserves.

I made coffee. Poured a glass of water. Started cooking eggs for breakfast, protein first, because I know from tracking that it gives me about three hours of stable energy before my next decision window. There’s a small cut on my finger that’s finally healing. I noticed it while cracking the eggs.

And then I did something I’d been putting off: I opened the KNMI De Staat van ons Klimaat 2025 report.

KNMI is the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, the official climate authority for the Netherlands. Every year they publish a diagnostic of what has actually happened, not projections or models, but measurements. Real data from weather stations across the country, year after year, building a picture of how the physical ground beneath us is changing.

I wasn’t expecting comfort. But I also wasn’t expecting the quiet precision with which the report confirms something I’ve been feeling in my body for a while now: we’ve crossed into a different climate regime, and most of our systems haven’t caught up yet.

So I’m writing this with my coffee, my eggs, and the report open on my screen. Not because I have answers, but because I think some of you might be feeling the same unease I am, and maybe it helps to see the data that explains why.

What the KNMI report actually says

The language in the report is restrained. KNMI’s job is to advise government, not to alarm the public, so they write carefully. But the data itself is stark.

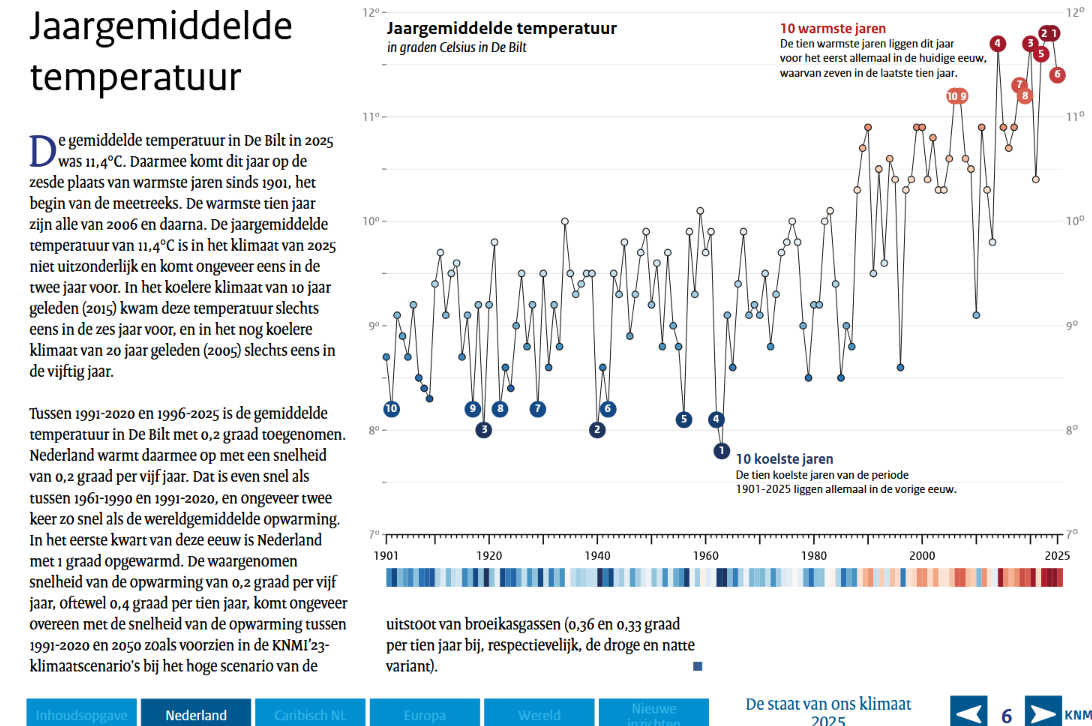

The Netherlands is warming nearly twice as fast as the global average.

Globally, we’ve warmed about 1.5°C since pre-industrial times. In the Netherlands, we’ve warmed 1.0°C just in the last 25 years, from 2000 to 2025. That rate is nearly double the global mean. This isn’t a projection. This is measured, at De Bilt and dozens of other stations, year after year.

Despite our wealth, despite our world-class water management infrastructure, despite our engineers and our planning, we are not insulated. We are front-row exposed.

2025 marks a structural shift.

For the first time in Dutch climate records, the ten warmest years ever recorded all fall within the 21st century. That’s not variability. That’s a regime shift. It means “normal” no longer exists as a stable reference point. Every system designed for the climate of the 20th century, our dikes, our agriculture, our housing, our energy grids, is now operating outside its original design envelope.

The risk isn’t desertification. It’s hydrological chaos.

2025 was the second sunniest year on record, the sixth warmest, and one of the ten driest summer half-years since 1906. High sunshine accelerates evaporation even when rainfall doesn’t completely collapse. The result is hydrological instability: dry soils, low river discharge in the Rhine and Meuse, agricultural stress, drinking water pressure, and inland shipping disruption.

We live in a delta. Water has always been our primary relationship with the physical world. And that relationship is changing faster than we’re adapting.

Extreme events are becoming more probable, not just more severe.

KNMI is explicit: events that used to happen once every 500 years now happen once every 15 years. They warn that new classes of extreme events are now plausible for the Netherlands, prolonged heat combined with power grid stress, multi-week cold snaps from a destabilized jet stream, Rhine discharge collapse, compound flooding with storm surge, and the emergence of diseases like West Nile virus that weren’t viable here before.

The calm is misleading.

2025 had five code orange weather warnings and zero code red. KNMI immediately stresses this doesn’t indicate safety, it indicates luck. This is a classic pattern before nonlinear escalation: the baseline shifts quietly, systems appear stable, and then thresholds are crossed rapidly.

What the report doesn’t say, but implies

KNMI doesn’t do politics. But if you sit with their conclusions long enough, certain realities become unavoidable.

Mitigation alone will not save system stability. Even if global emissions stopped tomorrow, the warming already baked into the system means adaptation is now unavoidable, not optional.

Dutch infrastructure was built for a climate that no longer exists. Everything from water management to agriculture to public health to housing is now running at the edge of its design capacity, and sometimes beyond it.

The future will be punctuated disruption, not gradual decline. We won’t slide smoothly into a warmer world. We’ll lurch from threshold to threshold, and each time we cross one, the rules change.

KNMI puts it plainly: “Het klimaat blijft veranderen en er komen dus nieuwe risico’s in beeld.” (”The climate will continue to change, and new risks are therefore emerging.”)

That one sentence quietly invalidates any narrative of return to normal.

How this connects to everything else happening right now

Here’s what I’ve been thinking about while eating my eggs and re-reading this report: climate isn’t a separate crisis. It’s a constraint that multiplies every other stress the system is already under.

The KNMI report is one measurement layer. But it sits inside a much larger pattern:

The Dutch government just locked in 3.5% of GDP for defense spending, legally anchored, long-term, non-negotiable. That’s a massive reallocation of energy and resources toward militarization.

Meanwhile, our political system is structured around polderen, consensus-building that worked beautifully when we had abundant resources and time to negotiate. But polderen requires slack. And right now, there is no slack.

Diaspora communities across the Netherlands are processing compounding grief, Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan, the Yazidi genocide. Institutional responses feel simultaneously over-promised and under-delivered.

And then there’s the healthcare system, where I work. We’re understaffed, overloaded, and running on the goodwill of workers who are increasingly burning out. I just finished my fifth consecutive shift. My HRV this morning dropped 19.5% from yesterday. My body is telling me what the system won’t admit: we’re spending reserves we don’t have.

These aren’t separate problems. They’re coupled.

When you understand constraints, real physical and energetic limits, a lot of what’s happening in the world starts making brutal sense.

The Netherlands cannot simultaneously:

Spend 3.5% of GDP on defense

Adapt all infrastructure for a new climate regime

Maintain current social services

Process collective trauma at scale

Preserve slow consensus decision-making

The math doesn’t close. Something will fail.

This is true not just for the Netherlands, but globally. Everywhere, institutions are facing the same bind: more problems, less energy, tighter constraints, slower adaptation. Climate is the pressure that reveals every other weakness in the system. It’s the constraint that says, “You can’t keep pretending you have infinite resources anymore.”

And once you see it that way, once you start reading the world through the lens of binding constraints, you stop being surprised by institutional paralysis, by the gap between what governments say and what they do, by the way suffering gets prioritized or ignored based on invisible calculations about which populations are “worth” protecting.

You start seeing managed decline: the strategy of accepting that full prevention is impossible, and shifting instead to damage control, prioritization of core functions, and crisis governance.

Whether they name it or not, that’s what’s happening.

What you can actually do with this information

I don’t have a neat solution to offer. I’m not going to tell you to vote harder, or buy an electric car, or start a rooftop garden, though none of those things are bad.

What I will say is this: your nervous system is not lying to you.

If you’ve been feeling a low-grade unease about the future, if you’ve been noticing that institutions feel less competent than they used to, if you’ve been struggling with decisions about whether to have children or where to live or how much hope to hold onto, you’re not broken. You’re perceiving accurately.

The ground is shifting. Faster than most people want to admit.

And the question isn’t whether you can fix it. You can’t. No individual can.

The question is: how do you maintain the capacity to see clearly, feel honestly, and act with integrity anyway?

For me, that’s meant building what I call observatories, structured ways of tracking what’s actually happening across different layers of reality. I track my own body’s regulation capacity. I track climate and political systems in the Netherlands. I track how news gets filtered and distorted. Not because I think I can control any of it, but because accurate perception gives me agency at the scale where I actually live.

Adaptation happens at the scale where energy can still couple to action. For most of us, that’s not national policy. It’s local: your city, your neighborhood, your community, the people you can actually reach and support.

When national governments are paralyzed by impossible trade-offs, municipalities become the adaptive layer. Amsterdam, Den Haag, Utrecht, these cities still have autonomy to build local climate resilience, create refugee support networks, develop community care protocols, and experiment with decision-making structures that don’t require everyone to agree before anyone can act.

That’s not romanticism. That’s thermodynamic necessity.

A final thought, from my kitchen table

I’m 32. I work in healthcare. I track systems. I support mutual aid for Gaza. And I’m trying to decide whether to bring a child into this world.

The KNMI report doesn’t make that decision easier. If anything, it confirms my hesitation is rational. The Netherlands I grew up in no longer exists climatically. The Netherlands a child born today would grow up in will be more volatile, more unstable, more tested.

But it also reminds me that hesitation and paralysis aren’t the same thing.

The work I’m doing, tracking, witnessing, building observation infrastructure, supporting adaptive action at the scale where it’s still possible, that work matters. Not because it will “save” anything in some grand sense, but because sustained, accurate perception is itself an act of resistance against the normalization of degradation.

Someone needs to say: “This is not okay. And I’m going to act as if it matters anyway.”

Maybe that’s you too.

If it is, I’m glad you’re here.

(source: KNMI )

If this resonated with you, consider subscribing. I write about systems, constraints, climate, healthcare, and what it means to witness managed decline without burning out. Not because I have all the answers, but because I think we figure this out together, or not at all.